The historic St Mary’s Church of Magheraculmoney Parish dominates the drumlin landscape of the quiet rural townland of Ardess Glebe. The name, Magheraculmoney, has been translated to “the plain of the back of the shrubbery” and “the plain of the peaty angle.” An Order of Council was issued on 27th February 1770, dividing the parish into two, with the second parish being called Drumkeeran.

The first rector of Magheraculmoney was recorded in 1439, and records state that the Church, also previously known as Templemaghery Church, was originally built during the fourteenth century and was subsequently burnt in 1484. Part of today’s present stone-built structure can be dated as far back as fifty years before the Reformation. In 1622 it was noted that the Church was lately roofed, but not glazed. It has since undergone extensive alterations and enlargements during the eighteenth, nineteenth and twentieth centuries. We gratefully received a grant from the Heritage Lottery Fund which allowed further extensive restoratoin works to be carried out on the exterior of the building in 2016.

Ardess Church with its three stage tower now stands proudly as a distinctive landmark. Directly beneath the Church lies the family vault of the Archdales, once one of Fermanagh’s significant plantation families.

The graveyard surrounding the Church is immediately recognisable as an ancient pre-plantation graveyard and it is estimated that there is a total of 433 marked grave headstones, flat slabs and crosses, with the oldest visible date being 1679. From 1608 until 1903 the graveyard served both Protestant and Catholic families in the district. All these graves face east with the exception of the priests’ graves who, according to local folklore, face west reportedly overlooking their flock. Running right across and dividing the pre-plantation graveyard in two is a huge fourteen foot wide trench grave. Described locally as the Famine Pit the huge long narrow sunken grave of 120 feet was used for burial during the Great Famine of 1845 – 1850. In 1997 Ardess Community Association marked the 150th anniversary of 1847 by restoring the unmarked famine pit and creating a sensitive memorial commemorating the many forgotten famine victims from North West Fermanagh, and in 2000 an ecumenical service of dedication and commemoration was held in the churchyard.

A former incumbent, the Revd Canon F.A. Baillie, Rector from 1979-1987, published Magheraculmoney Parish: A Short History in 1984.

—–

BBC ‘Your Place And Mine’

History from Headstones: Ardess

As part of a series of special features, Breege McCusker visits the 1000 year old graveyard at St.Mary’s, Ardess near Kesh…

In this visit to Ardess, Breege McCusker spoke to William Roulston (Ulster Historical Foundation), Mae Glenn, Dorothy Pendry, Mary Beard & Johny Cunningham.

William Roulston feels that Fermanagh excels in the quality of craftsmanship of its gravestones. “There’s probably nowhere in Ireland where you will see better” he says.Ardess has a wonderful setting for its church and graveyard is surrounded by green fields. There’s an old school yard and a 17th century rectory nearby. The present day church, which has been renovated in quite recent times, stands on the site of a much earlier church which probably dates back at least a thousand years. In the early part of the 17thC the church was taken over by the church of Ireland and has been used by it ever since but the graveyard has been used by all denominations. The church of St. Mary’s is known by different names by various parts of the local community and thus reflects all traditions. This parish has also been called by several different names. . A generation or so back it was known locally as Black Bog Parish. it was also known years ago as the Templemahery in the parish of Magheraculmoney in Ardess.

William believes that this churchyard has the earliest known example of sculpted headstones in Ireland. Not surprisingly then, it is here you will find the earliest sculpted headstone in N. Ireland Fashioned in the form of a Celtic cross, this stone is in memoriam of John McMulchan and bears the date 1679. There are about a dozen more headstones in this distinct style which clearly represents a school of masonry of that era. This particular style of stone can also be found in surrounding counties such as S Tyrone and even Donegal.

Mae Glenn’s ancestors came to this part of the world from the English/Welsh borders towards the end of the 1600s. Many of them are buried here. The Earliest marked Phillips family grave dates to around 1800. May tells of how, a couple of generations ago, people would have either walked to church or travelled by pony and trap. She also recalls that when she was a child she and her friends would have gone to a particularly scary vault close to where her parents are now buried. “As children we were mesmerized by it…” she says. “…before we went to Sunday school we would go up there and peek in and we would see some bones”.

Many years ago when May was a teacher, the Duke of Westminster came here as a young student, to write down the inscriptions around the graveyard. She says that everyone else in this graveyard is buried facing towards the east but he is buried facing west.. to keep an eye on his flock!

There is one huge grave in the Ardess churchyard which is “The Famine Grave”. Dorothy Pendry was a member of the community association which was responsible for putting this memorial in place. It came about at a time when the community was looking back at 150 years since the famine. It had been known for a long time that this famine “pit” existed but the upper part of the graveyard where it is sited had fallen into a state of wilderness. She explains how a lot of hard work, along with some help from the Fermanagh Trust returned the famine grave to a cared for state. It now allows people to appreciate more what it means and the heritage it represents.

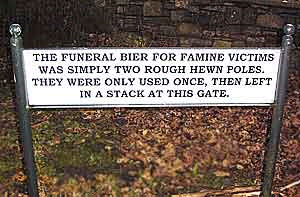

Large numbers of bodies were brought to this place from Irvinestown and the surrounding area. They were transported on funeral biers, which basically consisted of sheets with two poles to carry them with. The huge area of this mass grave is a very sobering sight and gives some sense of the large number of souls that perished. There is a vault here (which you can see in the above picture) which has been built in the style of a small cottage. This is to remind us of those typically small dwellings that the people of this community would have lived in back in the time of the famine.

Dorothy recounts a well known local story about Billy Mitchell from Ederney. Billy had the rather odious job of collecting bodies. Whilst perhaps an unpleasant task, this was a lucrative business. For every body he delivered, he was paid one shilling, which was a grand sum of money then. It is said that would sometimes have had one body on his cart and another on his back, thus doubling his pay for the journey. You might say he was a little greedy. The story tells how Billy had a lucky escape from what would have been a most unusual death. During the transporting of a body he decided to stop and take a rest at a bridge. While he was resting there, his barrow suddenly tipped up and the coffin it was carrying slipped off and almost carried Billy over the bridge to his death.

Local historian Johnny Cunningham says that his ancestors on his mothers side have been buried here for over 400 years. His family, The Eves, originally came over from east Anglia along with the Archdales during the plantation.

The oldest marked headstone to the Eves family was erected by John Eves to the memory of his father, Adam who was born in 1800.

As previously mentioned, this is a mixed graveyard but, unlike many others, there is no evidence any segregation between Catholic and Protestant graves. In the majority of mixed graveyards, The catholic graves would be found on one side and the Protestant ones on the other. In this burial place they are all intermingled throughout the site.

Johnny comments that this graveyard is also possibly unique in Ireland for its rich mixture of Scottish, English and Irish names.

A large vault stands in memory of the Archdales, who were the local landlords. There is also an Archdale vault outside the church and another underneath the church, where some 20 members of the Archdale family now lie.

Mary Beard Can also trace her family history back to the Archdales. Her great Uncle was Blackwood Archdale who lived in Castle Archdale with his son and daughter in-law, Harry and Audley Archdale. Mary remembers well going to the Castle as a as a young girl and describes what it was like. “It was a great place. You went up the steps to the front door and there was a big hall with an enormous staircase which had a stained glass window at the top.” She explains how the window was accidentally destroyed years later by one of the Archdale family who, having rescued the window and packaged it in a box, drove over it with a tractor.

Mary confirms the story that the Castle was haunted. She adds the detail that it was only haunted from the third floor upwards and how a black dog was often said to have been seen up there. She remembers how Audley tried to get her horse to go beyond the second floor and it wouldn’t go. Therefore it was agreed that it was haunted.

William Roulston describes a sandstone headstone which is a particularly fine example of Fermanagh sculpture.

This stone (seen on the right) was once located inside the church. It was moved to the outside during recent renovations. The stone bears the inscription: ‘Here lieth the bodies of Thomas and Elizabeth Humphries deceased 1703’, making it over 300 years old.

The headstone also has other obvious markings. In addition to an elaborately sculpted family crest at the top, it has carvings of the skull and cross-bones motif and an hour glass lying on its side. These are known as mortality symbols. There is also a Latin inscription which translates as “Remember you must die”. This, William explains, was to remind people of their mortality and to help them prepare themselves for death.

Similar “mortality symbols” can be seen elsewhere in Fermanagh such as in the graveyard at Pubble, near Tempo.